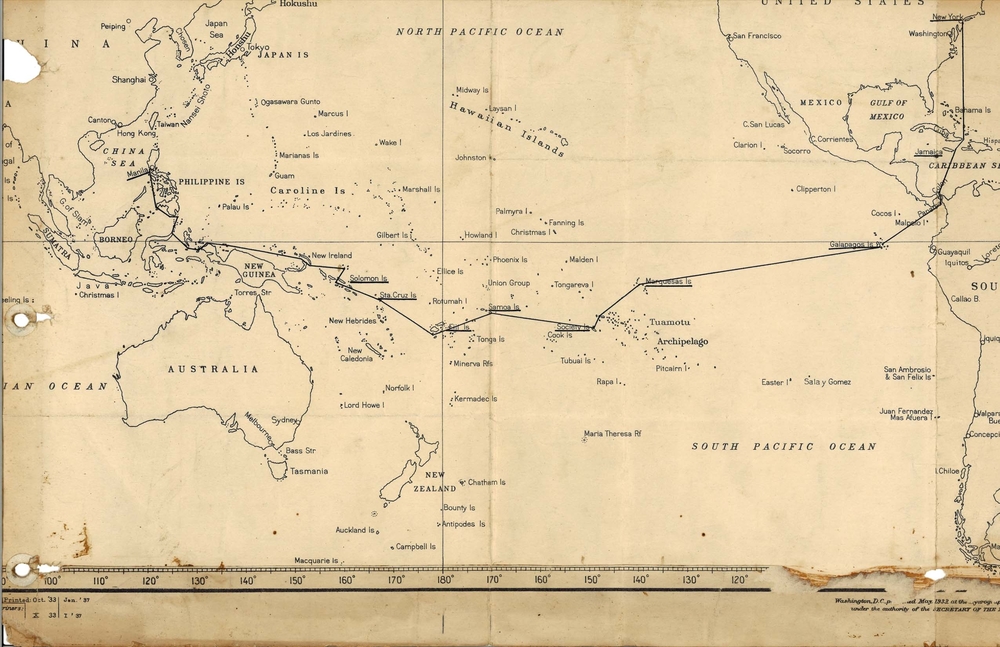

In December of 1936 a sixty-foot schooner named Chiva set sail towards Dutch New Guinea with funding from the Academy of Natural Sciences Philadelphia. Seven souls travelled for nine months through the Panama Canal, each with different goals for the voyage. The tale is one of active volcanoes, paradise birds, dense jungles, and the looming specter of cannibalism. Obviously it was great fodder for the daily newspapers of the time.

An aged binder sits in the Curious Vault, which contains many these clippings and pages of original photos from the Denison-Crockett Expedition, so named for its 29-year-old Captain Frederick Crockett and his wife Charis Denison-Crockett. Other notable adventurers were S. Dillon Ripley, a zoologist and the navigator George Adams, whose wife donated a trove of South Pacific materials to the museum in the 1976.

The clippings read like the trailer to a movie, describing the dangers they might face from cannibals, as well as the strange trinkets they carried to trade. Crockett packed soap because apparently the natives like to eat it, and corn cob pipes for them to blow bubbles. He also learned sleight of hand to impress them. One article makes note of the fact that two women were on board, making the trip notably progressive in at least one way.

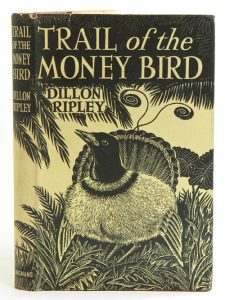

The reality of the voyage was a bit different from what the clippings suggest. Parsing through sensationalized media accounts can be tricky; much like the click bait of today, newspapermen of the mid twentieth century were sometimes trained to sell newspapers, not focus on boring realities. The best account we have of the journey is a book called Trail of the Money Bird: 30,000 Miles of Adventure with a Naturalist published in 1942, written by Ripley. It paints the voyage as a sort of quaint loll through paradise, with the ominous and ever present danger of cannibal natives. The audience for the book is clearly bird enthusiasts and fans of travel writing given the detailed descriptions of the specimen Ripley collected and countless tropical pastoral imageries. Treks like these don’t make it into the collective consciousness unless there is a discovery of colossal historical impact or a great tragedy, and the Denison Crockett expedition had neither (although one member of the team, Doan Nickerson, did die of an accidental gunshot wound).

Much like the newspapers, Ripley overplays cannibalism in the book, but in a letter back to the museum admits that it was mostly a lost practice at that point. In the correspondence, kindly shared by the archival staff of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia), he admits in a 1938 letter that, “the legend that white people are likely to be killed, ambushed or captured for eating, in the uncontrolled areas of places like New Guinea is, nowadays, only a legend.”

This is a product of what we now understand to be racist. Charis Crockett, an anthropologist in her own right, was actually on board to study the skull sizes of the South Pacific peoples, a pseudo-scientific practice known as phrenology that is now proven to be a prejudiced and outdated line of inquiry (and was even basically archaic in 1937). Much of the wording that Ripley utilizes in his book would be considered flat out racist today, describing the skin tones and facial features of the various peoples they encounter.

Ripley himself is an otherwise fascinating character. He was an spy in India and Pakistan during World War II serving as chief of the Office of Strategic Services, secret intelligence branch in southeast Asia. He went on to be the Secretary of the Smithsonian (the museum’s highest office) during its period of greatest growth and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan. No relation to the creator of Ripley’s Believe or Not, though on the Denison Crockett expedition many of those who took them in along their 30,000 mile voyage mistook him for the founder—a fact he was not quick to correct— and he was always the guest of honor. The New Yorker profiled the birder/spy in 1950, before his tenure as one of the most influential museum professionals in American history, and it is a fascinating read.

Along the way the navigator of the Chiva George F. Adams acquired a handful of artifacts, some of which are now secure in the Curious Vault. Oceanic Art is a complicated art historical tradition for a handful of reasons. For one, the countless different tribes also have countless different customs, each as subtle as the next. Like much of non-Western art, the culture is heavily object focused in Oceania, and the aesthetic often extends into the tattooing and body paint as well. The tradition includes several unique objects such skull houses, canoes, teeth beads, shields and war clubs.

Of particular note in the collection is a set of war clubs from the Solomon Islands. The clubs were typically used for ritual, but sometimes did get used for actual battle. They would have been carved and then soaked in mud for a month to give them a darker finish. They range from plain, to sharply incised designs. The original museum records claim the heavily decorated club with the flat end was used to kill sacrifice victims. This, can obviously, not be confirmed.

The most notable club is shaped like fish which upon further research revealed itself to be a bonito. The bonito fish is plentiful off the Solomon Islands and very important to puberty initiation ceremonies. Young men are expected to catch one, and hug the fish to their bodies as well as drink its blood. The fish then becomes a symbol of power and strength. There are also two paddles as well as an adze, which would have been quite valuable to a Solomon Islander in the 1930s, as metal was very scarce. Adams must have been a skilled negotiator.

Unfortunately information about George Adams is sparse, although we know he was a founding member of the sailing organization The Corinthians. We know that he acquired the objects that now lie in the Curious Vault. Not much is mentioned of Adams in the Trail of the Money Bird, mostly because his relationship with Ripley seems to have been somewhat begrudging. It appears Adams wasn’t much of a scientist, and didn’t really understand what the point of caging and transporting such an large amount of birds or the importance of the expedition altogether. Ripley says of the cages, and “I suppose, my presence on the boat, George could never rationalize in his mind. The important thing to him was the boat of which he thought so much.” He also claims that “like my bird-skinning board, my bird-box was an object of contempt and irritation to poor George.” So George, unfortunately, our museum’s gracious donor is mostly left out of the saga.

But an impressive handful of scientific research, mostly on birds— but also fish, reptiles, and amphibians as well— was completed because of the Denison- Crockett Expedition. The Curious Vault is proud to house the artifacts collected by the navigator of this notable adventure and the war clubs remain a reminder of a different time in a less connected world.

Special thanks to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University for their help in research.

The Curious Vault is an online cabinet of curiosities featuring objects from the collection of the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science, presented by writer Nathaniel Sandler and Kevin Arrow, Art & Collections Manager. For more information, email karrow@frostscience.org

Postscript: We have a lead on George F. Adams through The Corinthians, still active sailing organization, he was involved with throughout his life. We are trying to confirm if a gift he gave them, a piece of the rudder of the infamous HMS Bounty, has been verified and still with the organization. If anyone has any additional information about Adams please contact the museum.

Media Galleries

Photos