Some like it hot – and evolution might be the reason.

Have you ever been to a restaurant with someone that brags about their love of spicy food? While it might be satisfying to watch them occasionally bite off more than they can chew, consuming spicy food is uniquely baked into our evolutionary history. Humans are among the only animals that seek out spice, and our ancestors have pursued this particular culinary practice for thousands of years. There are remnants of a mustard-like spice on the pots of an archaeological site in Denmark dating back 6,000 years and coriander is seen in archaeological sites as early as 23,000 years ago.

David Julius

Ardem Patapoutian

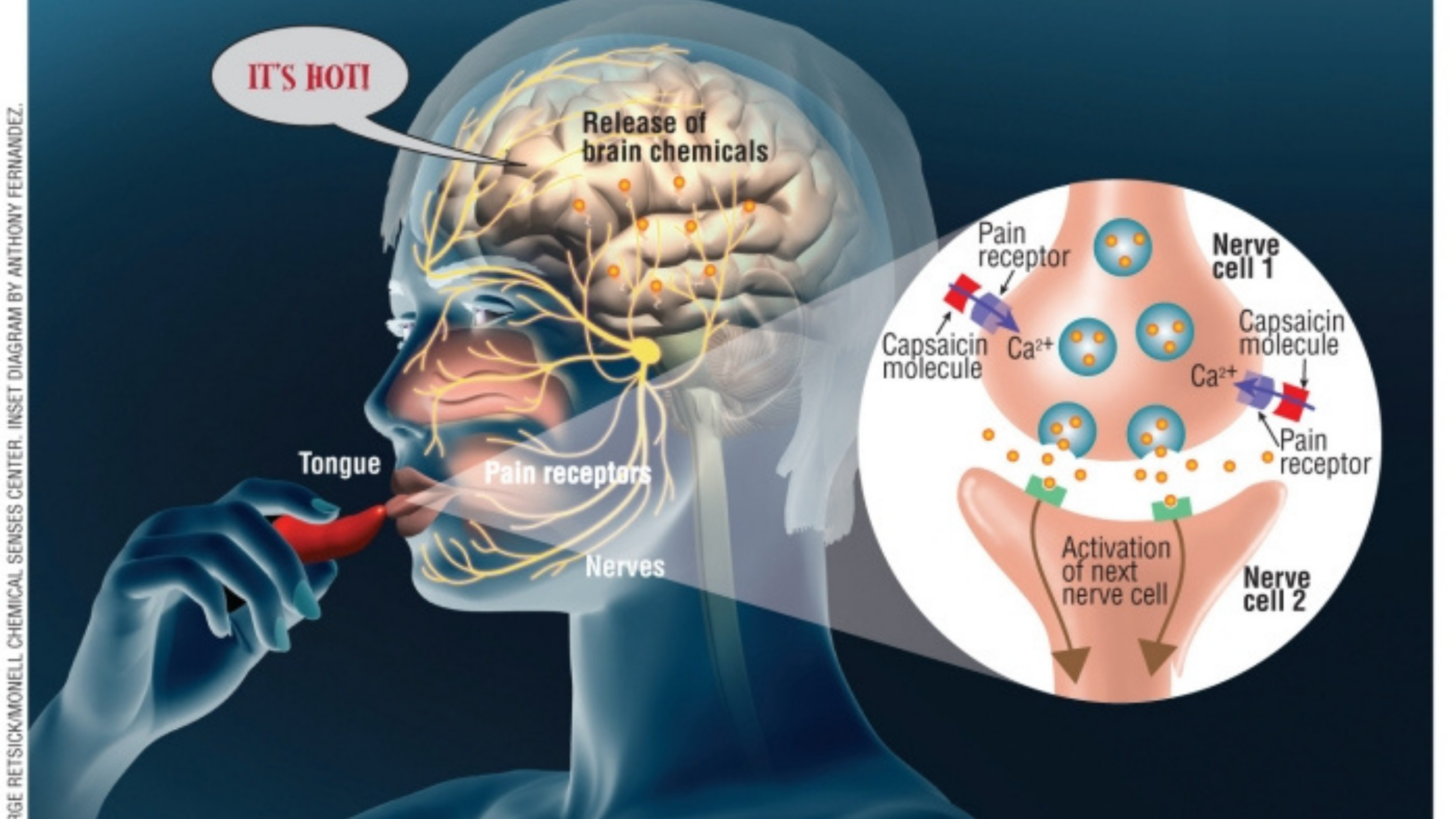

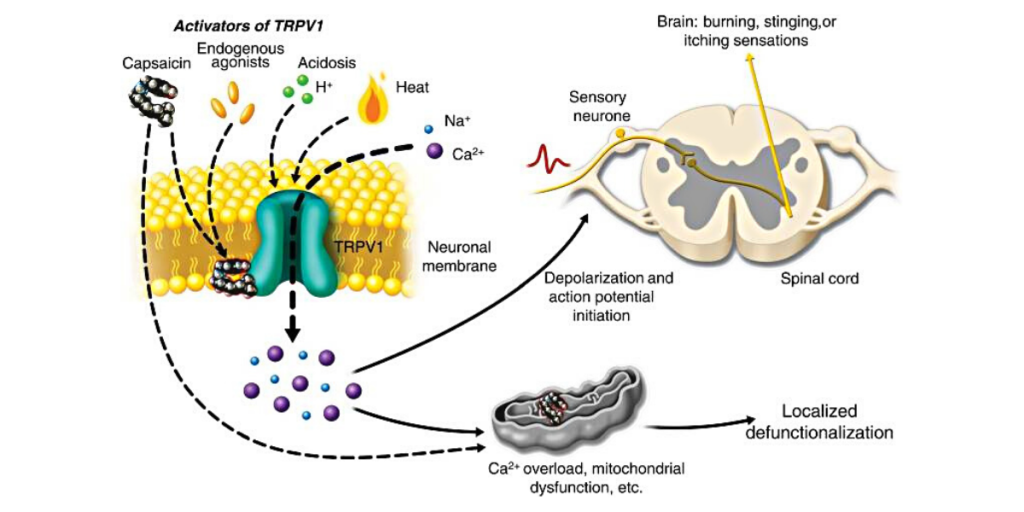

Recognizing heat, whether from a spicy pepper or a hot stove, is the job of pain receptors called nociceptors found in our mouths, joints and skin. Discovery and characterization of one of these receptors, TRPV1, earned David Julius the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology (shared jointly with Ardem Patapoutian). When TRPV1 in our skin detects a high temperature, typically over about 109 degrees Fahrenheit, it sends signals to local neurons who quickly convey that information to the brain. Other TRPV receptors respond to slightly warm temperatures and others still to extremely hot temperatures, allowing the brain to gauge the level of threat and respond appropriately. However, when capsaicin, the chemical compound in peppers that make them seem hot, binds to TRPV1, it lowers the temperature that triggers the response to about 95 degrees, significantly lower than the standard temperature in our mouths. If you’ve ever started sweating after eating a particularly spicy meal, it’s because your brain was receiving signals that you were in a very warm environment.

From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that animals who can quickly detect hot temperatures and avoid suffering severe burns would have a higher rate of survival than their less temperature-aware peers. It may be therefore be unsurprising that nociceptors have been detected in everything from leeches to rats. Capsaicin, which doesn’t actually harm animals, may have evolved in peppers as an evolutionary strategy to prevent predation by animals, activating animal’s nociceptors to discourage them from eating the fruit. In fact, some of the only animals that seem unaffected by capsaicin are birds, who just happen to be one of the best dispersers of pepper seeds. This may be an evolutionary adaptation for peppers to ensure that only animals that will disperse their seeds consume them.

So why did humans evolve with a love of peppers and other spicy foods? While hypotheses range from helping us sweat more efficiently to simply being more delicious, some scientists think human’s preference for spice might relate to antibacterial and antifungal properties of capsaicin. Researchers at Cornell studied the amount of spice in recipes across the world and found that spicy foods tend to be more popular in recipes near the equator. For example, onions are found in over 80% of recipes in India but only about 20% of recipes in Norway. These tropical locations have higher average temperatures, leading food to spoil more quickly, but traditional cooking spices can kill a significant number of potential bacteria and fungi. By adding a little bit of extra spice to their diet, our ancestors may have been able to prevent contracting a foodborne disease.

If you’re not a fan of spicy food, don’t despair. There’s growing evidence that increased exposure to capsaicin will eventually desensitize your TRPV1 receptors. In other words, if you eat enough spicy foods, you’ll eventually learn to tolerate it. If that sounds like torture, however, you can visit Frost Science for a milder experience that’s still rich in learning.

In Skin: Living Armor, Evolving Identity presented by presented by Miami Cancer Institute, part of Baptist Health, you’ll be able to conduct hands-on (literally) experiments with nociceptors, along with receptors for pressure and vibration. You’ll also be able to explore how humans respond to different environments and vary across the globe. It’s a great way to discover how our unique evolutionary history has shaped the adaptations on our skin.