Concrete. The word itself may not initially excite much inspiration – unless you’re one of those who knows something about it. Then the word transforms into a series of interrelated things – Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics (“STEAM” in museum-speak). For the construction of the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science, the precise science, engineering, and art of concrete becomes even more critical, and more interesting, due to the sheer complexity of the building itself. Baker Concrete Construction is responsible for making it all happen, and Ken Hover, an independent concrete consultant and Professor of Engineering at Cornell University now also assigned to the project, sat down with us to tell us all about it. Dr. Hover began his career as a military engineer, repairing deteriorating structures, but soon was more interested to know just what had caused the deterioration in the first place. This motivation led to a long career working on a multitude of construction projects, ensuring that structures are built to the highest standards. In regards to the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science project, he started the conversation with two statements that were amazing and inspiring in and of themselves.

The Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science is not just your everyday concrete building – it is destined for the covers of science and design publications.

The only commodity in the world used in greater capacity than concrete is water.

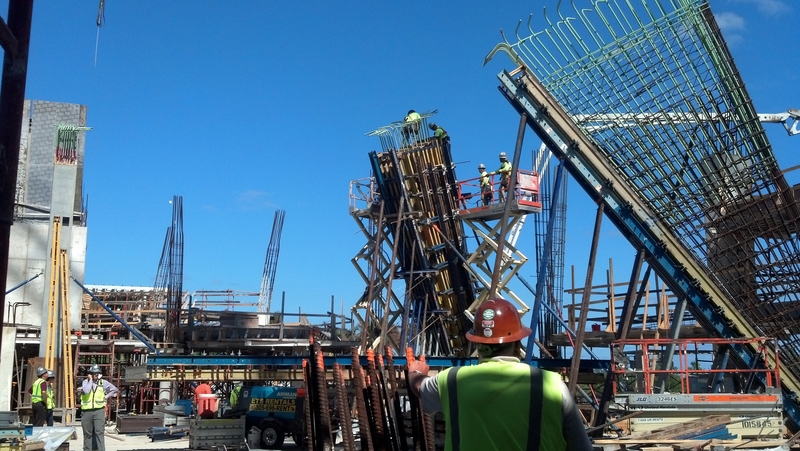

What makes the structure of the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science so special? Many building are made up of a series of rectangles, each story the same as the one below it. The Museum on the other hand, is made up of four separate buildings – each one is a different shape, each level is a different size, shape, height, or configuration from the one below it, and many parts of the structure are visible from every angle. From a concrete construction perspective, all of that means there is no repetition. Each story, column, beam, and floor needs to be individually considered in terms of engineering and aesthetics (remember, concrete is all about “STEAM”).

The uniquely shaped molds that will become the concrete columns supporting the Museum’s Gulf Stream tank

A central feature of the Museum will be the 500,000 gallon Gulf Stream aquarium tank, which will be supported by six unique concrete columns. What goes into making a single concrete column? First, you make the concrete itself, mixing cement powder, water, sand, and stone. (This recipe has not changed since Julius Caesar’s chief architect wrote it down over 2,000 years ago, but for this project, there are lots of additional additives to this concrete which make our mix special.) Then you test the consistency by pouring some out onto a flat board. As the concrete spreads, you check that it spreads evenly, and swirl it around to make sure that there isn’t any excess water. You create a mold for the column using wooden forms and steel beams, and then, you do not pour the concrete in to the top of the form mold. Instead, you pump it in from the bottom of the form, letting the concrete push itself up as it fills (this method minimizes air bubbles). After curing and another round of quality control for structure and aesthetics, the column is ready to serve its purpose.

It takes a mindboggling amount of concrete to construct any building, and there is a “carbon footprint” associated with making cement powder. But the Museum is taking every possible measure to be “green,” even in the construction process. We are using a material called “blast furnace slag” to minimize the amount of cement needed for the structure. This byproduct in the production of iron and steel had historically been discarded as waste, but when it was found to be chemically similar to cement and just as strong, it began to be used in the construction of environmentally friendly building projects, like the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science. This concrete technology is just one of the many reasons why the Museum is earning a Gold-Level LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification.

At the end of the conversation, Dr. Hover summed up the job of a concrete consultant and construction firm like this: Our job is to bridge the initial dream, the architectural drawings, and the reality of a building for everyone to enjoy. From the beautiful rendering of the finished Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science below, that seems like a big job.